Johannes J. (Hans) Duvekot

Erasmus University, Netherlands

Title: Current management of Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy (HDPs)

Biography

Biography: Johannes J. (Hans) Duvekot

Abstract

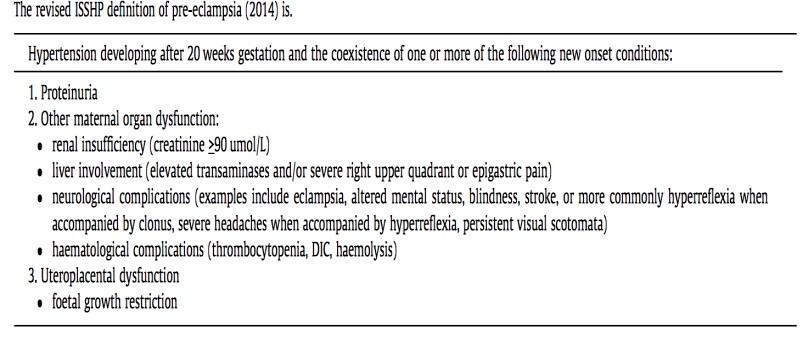

Introduction: Between 2 and 8% of pregnancies are complicated by preeclampsia (PE) defined as specified in table 1(1). At present, the only ultimate “cure” of PE and other forms of HDPs is removal of the placenta and thus, delivery. As the clinician provides “combined care” to 2 risk patients, treatment focuses on prevention of both maternal and fetal morbidity. In ≈1/3 of cases the dilemma arises that the prematurity risk outweighs maternal risks of ongoing HDP pregnancy. In ≈2/3 of cases, HDP symptoms develop >36 weeks with acceptable prematurity risks for the infant. However, at this later gestational age maternal risks are not lower! Most maternal deaths occur in the last half of pregnancy, even though the incidence of maternal death is 20-fold higher in early- onset PE. The latter is related to the much higher incidence of severe disease in early-onset PE. In developed countries PE accounts for ≈19% of maternal deaths (2).

Acute treatment: Severe HDP ought to be treated by a multidisciplinary team (obstetrician, neonatologist, and anesthesiologist). Initially, prompt stabilization by controlling blood pressure along with MgSO4 admini- stration to prevent eclampsia is of utmost importance. In most cases intra- venous administration of antihypertensives is needed. After reaching a clinically stable maternal condition, the clinician has to decide how and when to deliver the infant (2).

Temporizing management or not: In severe HDP temporizing manage- ment is only recommended after the 24th week. The best management of severe HDP between 28 and 34 weeks is still open to debate. After 34 weeks it is generally accepted to deliver women with severe HDP shortly after maternal stabilization. Between 34 and 37 weeks, temporizing management of mild HDP may be especially beneficial for the fetus (3). After 37 weeks induction of labor or elective cesarean section is strongly recommended (4). In the decision whether or not to prolong pregnancy, evaluation by a risk score may help to decide. The so-called “full-Piers” model gives some important clues for pending morbidity (5).

Table 1 (adopted from ref 1).

References:

-

Tranquilli A et al. The classification, diagnosis and management of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: A revised statement from the ISSHP. Pregnancy Hypertens 2014; 4: 97.

-

Steegers E et al. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet 2010; 376: 631.

-

Broekhuijsen K et al (HYPITAT-II study group). Immediate delivery versus expectant monitoring for hypertensive disorders of pregnancy between 34 and 37 weeks of gestation (HYPITAT-II): an open-label randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2015; 385: 2492.

-

Koopmans C et al. (HYPITAT study group). Induction of labour versus expectant monitoring for gestational hypertension or mild pre- eclampsia after 36 weeks' gestation (HYPITAT): a multicentre, open- label randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2009; 374: 979.

- von Dadelszen P et al. (PIERS Study Group.. Prediction of adverse maternal outcomes in pre-eclampsia: development and validation of the full PIERS model. Lancet 2011; 377: 219.